We live in cities surrounded by thousands of people, but we're still anonymous. It's like we've optimized everything for convenience and variety, but in the process, we've lost what it means to be a "local."

I remember this feeling vividly when I lived in Austin. For a while, it was perfect. Small community, local Greek cafe every Wednesday, same barista, same order, same seat, same faces. Then the city changed. High-rises everywhere, Amazon Go stores replacing corner shops. Everything became transactional.

But was that just the city's fault? Or had I stopped committing? One Wednesday, I tried a new cafe. Then another. I was optimizing for variety and convenience, keeping my options open.Within a year, I was anonymous again.

Have we become members of nothing because we commit to nothing? We treat each choice like we're keeping our options open, afraid that picking one place means missing out on something better. At the same time, we're lonelier than ever.

The antidote isn't another app or networking event. It's simpler, older, and hiding in plain sight. A third place that's yours.

In 1950s Greenwich Village, there was a working-class bar where a group of struggling artists faced the same problem you do today. New York was exploding with options… galleries, cafes, clubs all competing for attention. They could have networked everywhere, kept their options open, and optimized for the "best" spot each night.

Instead, they chose one dingy bar and showed up. Same booth, same time, night after night. It wasn't strategic. It was survival. The Cedar Tavern became their solution to anonymity while accidentally changing American art.

Issue forwarded by a friend? Subscribe here.

The Cedar wasn't much to look at. Dim lighting, cigarette smoke thick enough to cut with a knife, cheap beer, sticky floors. It's a place you would walk past without noticing.

These weren't established artists. They were broke, unknown, and surrounded by thousands of other artists competing for the same gallery spots. The city was isolating. Success felt random. And they needed stability somewhere.

Every night, around 9 pm, Jackson Pollock, a struggling painter who couldn't afford his own studio, would slide into his booth. Always the same one, back left corner. Other broke artists like Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline had their spots, too. De Kooning would sit near the bar. Kline would show up later, taking his usual stool. The bartender, John Bodnar, would already be pouring their drinks before they ordered.

Pollock was known for starting fights when he had too many. De Kooning would sketch on napkins, leaving drawings scattered all over the place (that would later sell for thousands). There were unspoken rules that everyone understood. You didn't sit in Pollock's booth. You didn't interrupt when painters were arguing about color theory at 11:34 pm.

Bodnar was the institutional memory of the place. The one constant as artists came and went, succeeded or failed, sober or not. But it's not about the booze, or even the conversations. It's the ritual. Showing up at the same time. Sitting at the same spot. Ordering the same drink.

The consistency created something none of them could have built alone. Not just art connections, but belonging. Someone who knew their drink, their struggles, their patterns. The opposite of anonymous.

Abstract Expressionism didn't happen without the arguments over beers at the Cedar Tavern. But more importantly, these artists weren't lonely anymore. They had become regulars.

You earned it by coming back, night after night, until you were woven into the fabric of the place (or spilled your drink on the sticky floors).

This is what sociologists call the "weak ties" phenomenon. Counter-intuitively, the casual connections you build by showing up consistently to the same place (nodding at familiar faces, chatting with the bartender) create stronger community bonds than the "strong ties" we engineer through networking events or organized meetups.

Because weak ties aren't forced. They grow organically through proximity and time. You can't fake them or speed them up. The bartender who knows your drink, the regular who nods when you walk in… these relationships feel low-stakes but accumulate into real belonging. None of those artists planned to form a movement. They just needed a place where they weren't anonymous.

Having "your seat" is built on territorial consistency. In turn, that breeds familiarity, familiarity breeds trust, and trust breeds belonging.

First, pick one place within walking distance. It doesn't have to be the trendiest spot. It's gotta be a neighborhood institution that's been around for years. The kind of place that has the same bartender/barista from five years ago.

Next, commit to going the same day and time for the next three months. Your body and the space need to recognize each other. Always sit in the same area. Learn the staff's name within the first few weeks that you go.

Then, order the same thing for your first five visits. You're not being boring, you're being strategic. The staff needs a simple way to understand who you are first. When the bartender can pour your drink before you ask, or when the server knows you take your coffee black, you've crossed the threshold... you're not a customer anymore.

Always acknowledge other regulars with a slight nod. Some people come to their local spot for solitude, and that's to be respected. You're building parallel presence, not forced friendship.Most importantly, come alone most of the time. Practice being comfortable in public solitude. Bring a book or a notebook. Put your phone in your pocket.

The magic isn't immediate. You might wonder if you're the weird person who keeps showing up alone. Then one night, the bartender will have your drink ready when you walk in. Another regular will nod at you. Someone will ask where you were last week... you'll realize you're not anonymous anymore.

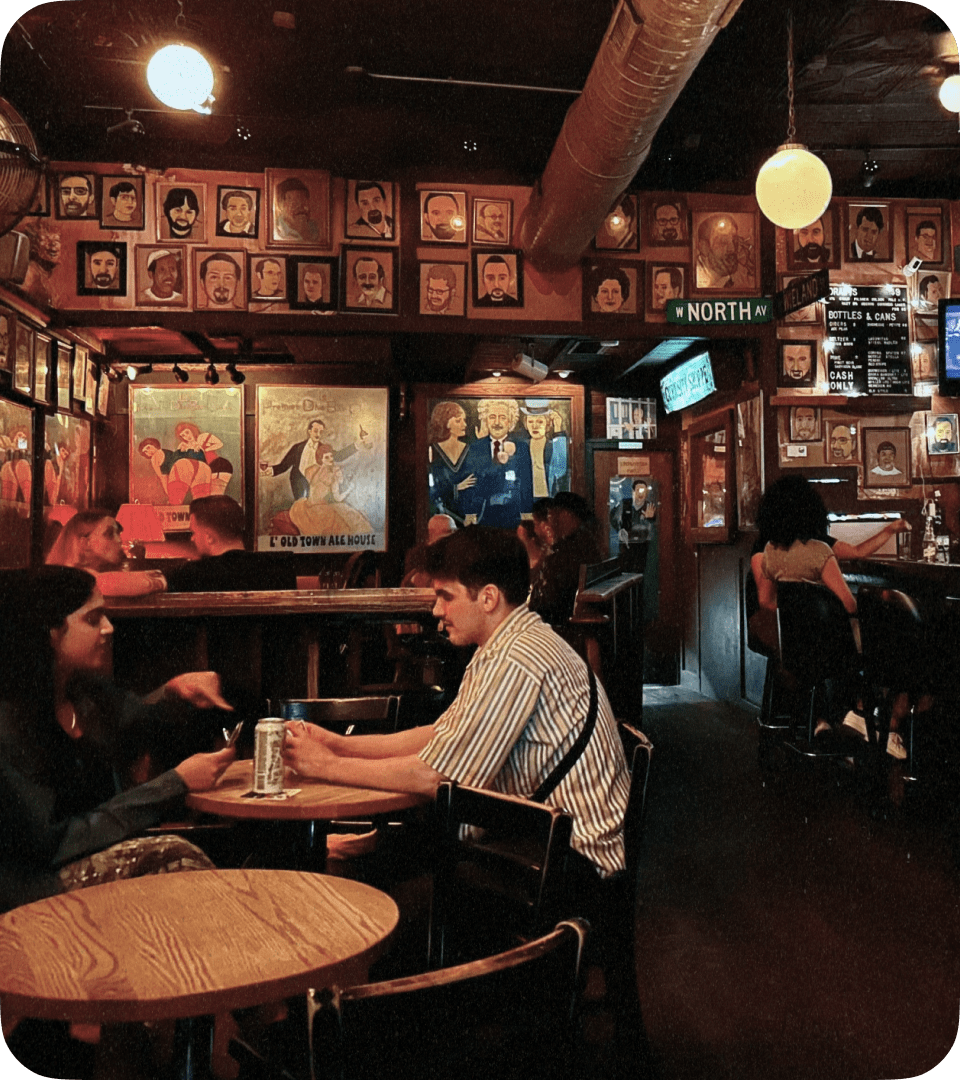

Green flags to look for: regulars who have their own glasses or mugs behind the bar, staff members who have been there for years, slightly worn furniture that's comfortable, cash-only operations, a corner where the same person sits every time you visit, and photographs of regulars on the wall.

Red flags to avoid: too much turnover in staff, overly designed spaces, places that change their menus seasonally to stay "relevant", and anywhere that markets itself as "workplace friendly."

Places like Cedar Tavern didn't die when it closed in 2007. There are still famous establishments that operate right now across the US. And they're easy to find once you know what to look for.

In Philly, John Doyle has worked the same Saturday shift since April 1974. Fifty years, same bar, same 11 am to 5 pm window, same regulars who've watched each other's kids grow up and have kids of their own. He won Best of Philly's "Best Bartender" award not for his cocktails but because he knew everyone's name and their usual orders. The bar opened in 1860, and it's Philly's longest continuously operating tavern.

In San Francisco's North Beach, three generations of family ownership maintain a strict policy: new partners must serve an eight year apprenticeship as a bartender first. Ron Minolli has been there for 30 years and knows all the regulars, their parents, and even their grandparents. It's hosted the same 8-Ball Pool Tournament every March for 53 years. Winners' names go on wooden plaques and are displayed throughout the bar. On Thanksgiving, they even serve Turkey on the pool table for regulars who are far from home.

In Chicago, Bruce Elliot spent 44 years as a regular at Old Town Ale House before buying it in 2005. When a fire damaged the bar in 1971, forty regulars physically carried the 60 year old mahogany bar across North Avenue themselves rather than let it close for even a day. Elliot hangs painted portraits of current regulars on every available wall. The bar has become a gallery of its own community.

If your city lacks a place like this, you can create it. Pick a spot. Invite three or four people. Make it the same time every week. Never move locations. Let it grow organically. Don't force it or try to make it a "thing." The consistency is what matters. Eventually, you'll have built what you couldn't find.

We're lonely because we've forgotten how to be findable. We keep our options open, which means we're never anywhere long enough for anyone to find us.

The Cedar Tavern regulars weren't special. They just showed up. Same booth, same time, until they were part of the fabric.

Belonging isn't given. It's earned through consistency. You can't shortcut your way to community through apps. You become a regular by coming back.

Having a place where, if you didn't show up, someone would notice. Where you're expected. Where you're known. Where life feels less like scrolling and more like living.

That's what the Cedar Tavern was. That's what your local could be.

Thank you for reading! Let us know what you thought of this issue by replying directly to this email. Cheers 🥂

Join 2,568 readers 💃🕺🏽